Million-Dollar Machines Running on Obsolete Code

Picture this: you're standing in front of a £3 million MRI scanner in a state-of-the-art hospital, watching a radiographer carefully boot up what appears to be a computer that wouldn't look out of place in a 1990s office.

Recent investigations into NHS cybersecurity have revealed some shocking evidence of cybersecurity lapses. This included staff operating CT scanners running Windows 7, according to Mohammad Waqas, principal solutions architect at Armis, speaking to The Evening Standard, and in one particularly alarming case, "staff members were streaming Netflix on the computer running an MRI machine".

These are not isolated incidents. From Germany's high-speed trains to Britain's electricity grid, critical infrastructure depends on software that predates the smartphones in our pockets. In 2024, Deutsche Bahn, Germany's railway service, posted a job listing for an IT systems administrator to maintain driver's cab display systems on high-speed and regional trains, with a surprising requirement: applicants needed expertise with Windows 3.11 and MS-DOS – "systems released 32 and 44 years ago, respectively," as the BBC’s Thomas Germain reported in May this year.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, San Francisco's Muni Metro light railway won't start up in the morning until someone "sticks a floppy disk into the computer" that loads MS DOS software on the railway's Automatic Train Control System, according to Germain’s article. The San Francisco Municipal Transit Authority “announced plans to retire this system over the coming decade, but today the floppy disks live on,” a daily reminder that critical infrastructure sometimes runs on technology that most people consider extinct.

More Common Than You'd Think (Or Hope)

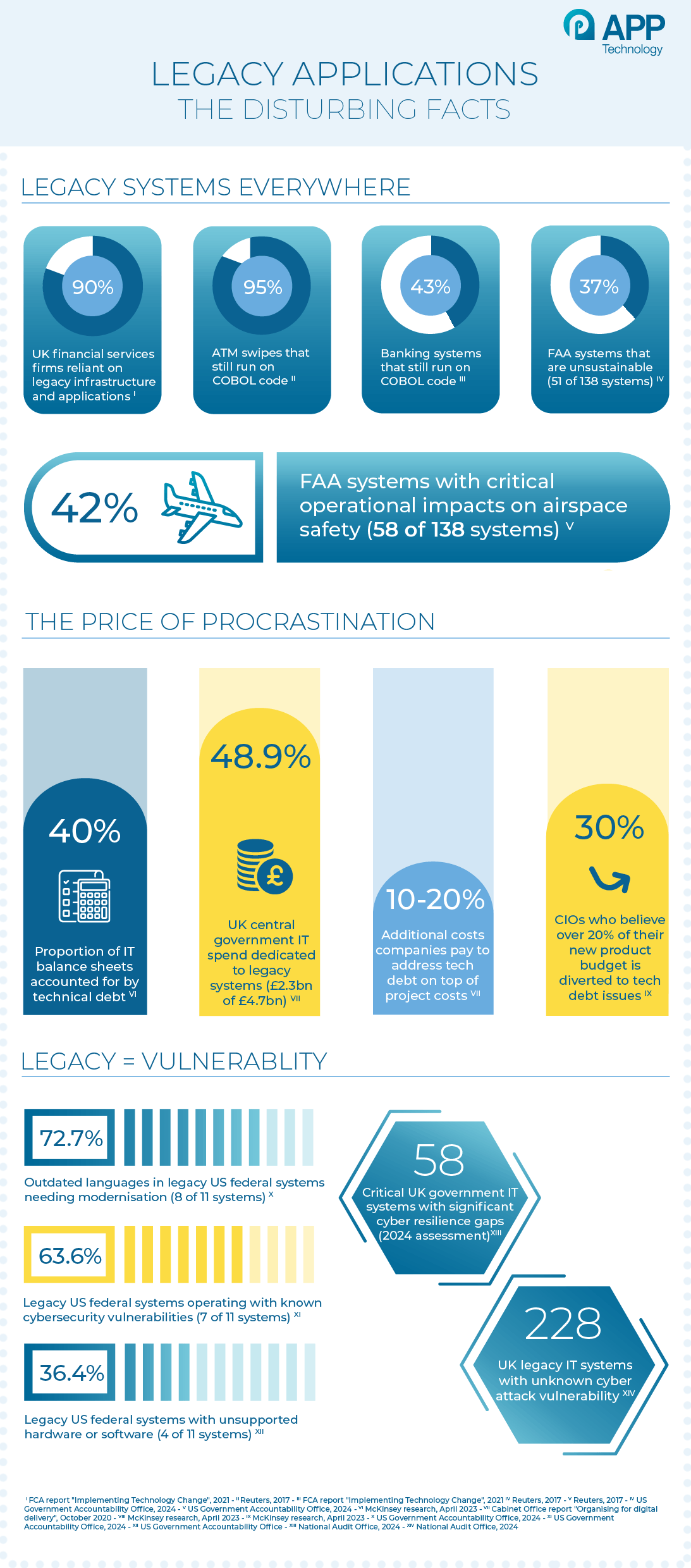

The scope of this problem extends far beyond these quirky examples. Independent analysis has revealed the true scale of legacy system dependence across critical infrastructure. The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) determined that 51 of the Federal Aviation Administration's 138 systems are unsustainable, "citing outdated functionality, a lack of spare parts, and more." Even more concerning, 58 of these systems "have critical operational impacts on the safety and efficiency of the national airspace," according to a GAO report, yet some modernisation projects won't be complete for another 10-13 years.

Closer to home, Britain's electricity grid faces similar challenges. The systems software for the National Energy System Operator (Neso), responsible for supplying electricity to the national grid from multiple energy sources, was developed in the 1980s. While these systems allow control room staff to balance supply from wind power and gas stations, "there are increasingly frequent outages on the system that connects the Neso control room with the control systems of power stations. When this happens, Neso staff must revert to notifying their instructions by telephone," The Telegraph’s Kathryn Porter reported in June 2025.

The financial services sector provides perhaps the most striking example of legacy dependence. The self-styled "COBOL Cowboy", 82-year-old Bill Hinshaw, still runs a thriving consultancy business for COBOL (Common Business Oriented Language), a programming language that debuted in 1959. His confidence isn't misplaced – according to Reuters research, 95% of ATM swipes and 43% of banking systems still run on COBOL code, with billions of lines still in active use today.

The Mounting Cost of 'It Still Works'

The financial implications of this technical debt are staggering. According to McKinsey research, technical debt "accounts for about 40 percent of IT balance sheets," with companies paying "an additional 10 to 20 percent to address tech debt on top of the costs of any project." Perhaps most tellingly, "30 percent of CIOs surveyed believe that more than 20 percent of their technical budget ostensibly dedicated to new products is diverted to resolving issues related to tech debt."

The UK government's own analysis provides a sobering perspective on these costs:

Cabinet Office report, "Organising for digital delivery"

Despite this enormous investment, the Home Office, with the largest single technology spend, "has not been able to retire any of their twelve large operational legacy systems" after 3-4 years of effort, the same report noted.

This pattern repeats across industries. Manufacturing facilities invest millions in cutting-edge equipment, only to discover that the control systems binding everything together represent the weakest link in their operational chain. The pharmaceutical industry faces particularly acute challenges, where any change to underlying systems requires costly re-validation to maintain FDA compliance, creating powerful incentives to avoid modernisation entirely.

The Hackers’ Playground

Even more alarming than the direct costs are the cybersecurity implications.

The National Audit Office's assessment of UK government cyber resilience paints an equally concerning picture. According to Computer Weekly's reporting on the NAO findings, the NAO study found that "58 critical government IT systems assessed in 2024 had significant gaps in cyber resilience," and more troublingly, "the government does not know how vulnerable at least 228 'legacy' IT systems are to cyber attack." The real-world consequences of these vulnerabilities are becoming increasingly apparent, with cyber attacks causing massive operational disruption and financial costs.

In the USA, the GAO's analysis of federal systems revealed that of 11 legacy IT systems most in need of modernisation, "eight use outdated languages, four have unsupported hardware or software, and seven are operating with known cybersecurity vulnerabilities." The Treasury Department's systems exemplify this challenge, running on COBOL and Assembly Language Code – "programming languages that have a dwindling number of people available with the skills needed to support them," according to the GAO report.

Your critical legacy systems CAN run securely on modern Windows networks.

For over a decade, we've tackled every application compatibility challenge thrown our way and we've never met one we couldn't solve. From early 1990s software to mission-critical systems across retail, education, pharmaceutical, nuclear, agriculture, transport, and finance sectors, we've proven that legacy doesn't mean liability.

Beyond Government: The Private Sector Reality

The private sector faces identical challenges. An oft-quoted report by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in 2021 found that over 90% of firms in the UK finance sector were “reliant on legacy infrastructure and applications to deliver production services”.

Recent UK government research commissioned by the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology discovered serious remote code execution vulnerabilities in enterprise connected devices, including IP cameras, VoIP phones, and NAS storage devices. The study found these devices "running outdated software, with one device's bootloader being over 15 years old". Vulnerabilities were widespread across products from all manufacturers tested. Crucially, according to the report, "only three manufacturers were able to remediate identified vulnerabilities and release fixes in the form of firmware updates."

In the nuclear industry, safety-critical systems installed decades ago must continue operating reliably for the entire lifespan of a facility. These systems may have been built using the best available IT at the time, but that technology was always doomed to become obsolete long before the facility itself.

Sellafield’s IT systems have repeatedly been found vulnerable to unauthorised access and loss of data. The former nuclear plant in Cumbria, now the world’s largest processor of radioactive waste, remains under "significantly enhanced attention" for cyber security according to a BBC report earlier this year, following cybersecurity shortfalls over a four year period for which the company was fined £332,500 plus costs in 2024.

Sellafield image credit: Simon Ledingham, CC BY-SA 2.0, Link

One of the most high-profile recent cases of legacy systems being exploited was when US network monitoring software company SolarWinds was the victim of a massive cyberattack, allegedly the work of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), in which hackers injected malware into an update that found its way to thousands of organisations, including the US government.

“Neither SolarWinds nor its customers knew that any sort of breach had occurred,” explained Brett Daniel in an article from January 2021, until “more than a year after the hackers initially gained access to SolarWinds’ build environment and nine months after the first poisoned update was released.”

The Digital Ball and Chain

Here lies the central paradox facing modern organisations: even the most technologically advanced companies can find themselves most constrained by legacy systems.

This creates a form of technological archaeology, where IT teams maintain systems they inherited rather than chose, supporting business processes they didn't design, using technologies they never intended to learn. The skills required become increasingly rare and valuable, concentrated among a shrinking pool of specialists who can command premium rates for their expertise.

The ripple effects extend throughout supply chains. Just-in-time manufacturing, which has driven efficiency improvements across industries, becomes a liability when it depends on systems that might fail without warning. The interconnected nature of modern business means that a legacy system failure at one supplier can cascade through multiple industries.

The High Price of Doing Nothing

The temptation to continue deferring modernisation is understandable. As long as systems keep running, why fix what isn't broken? This logic works until it doesn't, and when these systems fail, they tend to fail spectacularly and at the worst possible moments.

There's a deeper cost to the make-do-and-mend approach: IT teams spending their time firefighting legacy system problems aren't building new capabilities. Budgets consumed by increasingly expensive support contracts for obsolete systems aren't available for strategic investments. Perhaps most critically, the mental bandwidth consumed by constantly managing legacy system risks isn't available for forward-thinking strategic planning.

But how do you justify spending money to replace something that, despite its flaws, continues to function?

Calling Time on Legacy Apps

The evidence suggests that this balance is becoming increasingly untenable. Cybersecurity threats are evolving faster than legacy systems can be secured. Skills required to maintain obsolete systems are disappearing as specialists retire. Hardware components are becoming impossible to source. Regulatory requirements are tightening around system security and resilience.

The question facing every organisation isn't whether these legacy systems will eventually need to be addressed – they will. The question is whether that addressing will happen on your terms or on theirs. Whether it will be a planned, managed transition or an emergency response to a critical failure. Whether it will be an investment in your organisation's future or a desperate attempt to salvage its present.

The railway systems requiring floppy disks, the power grids running on 1980s software, the medical devices streaming Netflix – these aren't just technological curiosities. They're canaries in the coal mine, warning us that the foundations underlying our most critical systems are more fragile than we care to admit. In a world increasingly dependent on digital infrastructure, perhaps the most dangerous assumption we can make is that yesterday's solutions will continue working tomorrow.

Secure Your Legacy Applications

Did you know there is an award-winning, patented container technology that can safely integrate your legacy applications into a state-of-the-art 2025 estate for minimal cost and maximum peace of mind, without compromising ease of use? Don't believe it's possible? Call us for a demonstration.